Assets form the foundation of every business's financial structure, representing the valuable resources that companies control to generate revenue and build long-term value. Understanding what is an asset in accounting proves essential for anyone involved in business operations, financial analysis, or investment decision-making, as these resources directly impact a company's net worth, borrowing capacity, and growth potential. From tangible items like buildings and equipment to intangible resources like patents and trademarks, assets encompass diverse resources that share a common characteristic—they provide economic benefits to their owners. The accounting treatment of assets follows specific principles and standards that ensure consistency across financial statements, enabling stakeholders to evaluate companies objectively. Whether you're a business owner tracking resources, an investor analyzing financial health, or a student learning accounting fundamentals, grasping asset concepts helps you interpret balance sheets accurately and understand how businesses create and preserve value. This comprehensive guide explores the asset definition, classification systems, valuation methods, and practical implications that make proper asset accounting crucial for financial transparency and business success.

What Is the Definition of an Asset in Accounting

In accounting, an asset is a resource controlled by an entity as a result of past events from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity, according to the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). This formal definition highlights several critical characteristics that distinguish assets from other business items.

The Core Characteristics of Assets

What is considered an asset in accounting requires meeting specific criteria beyond simple ownership. Assets are resources controlled by the enterprise as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the enterprise. Control represents the key concept—businesses don't necessarily need legal ownership to record an asset, but they must control the economic benefits that resource provides. The future economic benefit requirement means assets must contribute to generating cash inflows or reducing cash outflows. An asset is something of value that a company expects will provide future benefit, whether through direct revenue generation, cost reduction, exchange for other assets, or settlement of liabilities. Without this future benefit expectation, a resource doesn't qualify as an asset regardless of its current value.

Assets in Simple Terms

Understanding what is an asset in simple words helps clarify this sometimes complex concept. An asset is anything a business owns that has measurable value and can contribute to earning money or provide utility over time. Think of assets as the resources available to a business for conducting operations, generating sales, and ultimately creating profit. These resources range from obvious items like cash in bank accounts to less apparent assets like money customers owe for purchases made on credit. If a business can sell it, rent it, use it to generate revenue, or has a future economic benefit from it, it likely qualifies as an asset.

The Accounting Equation and Assets

Assets play a central role in the fundamental accounting equation: Assets equal Liabilities plus Equity. This mathematical relationship forms the foundation of double-entry bookkeeping and must always remain balanced on a company's financial statements. This equation relates assets, liabilities, and owner's equity, demonstrating that everything a business owns (assets) is financed either through borrowing (liabilities) or owner investment (equity). Understanding this relationship helps explain how businesses fund their asset acquisitions and how asset changes affect overall financial position.

Types of Assets: Understanding Classification Systems

Assets are classified in multiple ways depending on their characteristics, with each classification system serving specific analytical purposes. Understanding these categories helps businesses organize financial information logically and enables stakeholders to assess different aspects of financial health.

Current Assets: Short-Term Resources

Current assets are short-term resources a business expects to convert into cash, sell, or use up within one year or one operating cycle, whichever is longer. These assets provide the liquidity necessary for daily operations and meeting short-term obligations. Cash represents the most liquid asset, including currency, checking accounts, and highly liquid investments that mature within three months, providing immediate purchasing power. Cash equivalents include money market funds, treasury bills, and other short-term investments easily convertible to known amounts of cash with minimal risk of value change. Accounts receivable represents money customers owe for goods or services delivered on credit, reflecting revenue earned but not yet collected and playing a crucial role in businesses that extend payment terms. Companies typically report receivables net of an allowance for uncollectible accounts, recognizing that some customers may fail to pay. For product-based businesses, inventory represents goods held for sale and constitutes a major current asset requiring regular valuation, including raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods. Prepaid expenses represent advance payments for goods or services to be received in future periods, such as prepaid insurance, rent, or subscriptions where payment precedes the benefit received.

Non-Current Assets: Long-Term Resources

Non-current assets, also called fixed or long-term assets, are resources businesses use over extended periods to generate revenue. You cannot easily convert them into cash, but they remain essential for operations and growth. Property, plant, and equipment (PPE) includes tangible long-term assets like land, buildings, machinery, vehicles, and furniture that support business operations over many years, gradually contributing their cost to expenses through depreciation. Land stands apart from other PPE because it doesn't depreciate—its useful life is considered infinite—while buildings, equipment, and vehicles lose value over time as they wear out or become obsolete. Intangible assets lack physical form but hold significant economic value for businesses, including patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade names, software, and brand recognition that contribute to competitive advantage and revenue generation. Understanding what is goodwill in accounting provides insight into one of the most significant intangible assets that arises when companies acquire other businesses for amounts exceeding the fair value of identifiable net assets. Businesses sometimes invest cash in securities they intend to hold beyond one year, with these long-term investments—including stocks, bonds, and real estate purchased for appreciation rather than operations—qualifying as non-current assets expected to generate returns over time.

Tangible Versus Intangible Assets

Assets can be classified by physical existence into tangible and intangible categories, each with distinct characteristics and valuation challenges. Tangible assets are physical items such as equipment and inventory that can be touched, seen, and measured, including cash, real estate, vehicles, machinery, inventory, and office furniture—resources with clear physical form. The tangible nature of these assets generally makes valuation more straightforward since markets exist for most physical resources, providing reference points for determining fair value, though depreciation and condition assessment still require professional judgment. Intangible assets are nonphysical items such as patents and trademarks that still hold value, including intellectual property, customer relationships, proprietary technology, and brand reputation—resources lacking physical substance but providing competitive advantages. Valuing intangible assets presents challenges since no active markets exist for many unique intellectual properties, with companies often relying on specialized valuation techniques considering factors like future cash flows, relief from royalty payments, or cost to recreate the asset.

Operating Versus Non-Operating Assets

Classification by usage distinguishes between assets directly supporting core business activities and those serving other purposes. Operating assets are resources businesses use in day-to-day operations to generate revenue, including cash for transactions, inventory for sale, equipment for production, buildings housing operations, and intellectual property supporting product development. Understanding operating assets helps stakeholders evaluate how efficiently businesses deploy resources to generate sales, with metrics like return on assets and asset turnover ratios providing insights into operational effectiveness. Non-operating assets don't directly support core business activities but still provide value, such as excess real estate, investments in other companies, and surplus equipment not currently used in operations. While non-operating assets may generate some return through rental income or investment gains, they don't contribute to primary revenue-generating activities, and businesses sometimes sell non-operating assets to raise capital or eliminate maintenance costs.

How Assets Appear on the Balance Sheet

The balance sheet presents a snapshot of a company's financial position at a specific point in time, with assets prominently featured in a structured format that facilitates analysis.

Balance Sheet Structure and Asset Presentation

Assets are reported on the balance sheet and are typically presented in order of liquidity—how quickly they can be converted to cash. This organization helps users quickly assess a company's ability to meet short-term obligations and understand resource composition. The balance sheet groups assets into major categories with current assets appearing first, followed by non-current assets. Within each category, specific asset types are listed, often with current assets organized from most liquid to least liquid.

Asset Classifications Required by GAAP

Additional sub-classifications are generally required by generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), which vary from country to country. These requirements ensure consistent presentation across companies, enabling meaningful comparisons. Standard asset categories include cash and cash equivalents, accounts receivable, inventory, prepaid expenses, property and equipment, intangible assets, and long-term investments. Notes accompanying financial statements provide additional detail about significant assets.

Understanding the Asset Section

Reading the asset section of a balance sheet reveals critical information about business resources and financial health. High cash balances suggest liquidity strength, substantial accounts receivable indicates credit sales volume, and significant property and equipment reflects capital investment in productive capacity. Comparing assets to liabilities reveals solvency—whether a company possesses sufficient resources to cover obligations. A business with more assets than liabilities is considered to have positive equity or shareholder value. If assets are less than liabilities, a company has negative equity.

Valuing Assets: Methods and Principles

Accurately determining asset values is essential for reliable financial reporting and informed decision-making. Different valuation methods apply depending on asset type and accounting principles followed.

Historical Cost Principle

The historical cost method bases asset value on original purchase price. For example, if a business buys a building for one million dollars, the building's value on the balance sheet will remain one million dollars unless adjustments such as depreciation are applied. This method provides objectivity and verifiability since original costs come from actual transactions with supporting documentation. However, historical cost doesn't reflect current market values, potentially understating or overstating economic worth as time passes and market conditions change.

Fair Market Value

Fair market value represents the price an asset would command in an arm's-length transaction between willing, knowledgeable parties. This approach provides current economic value but requires professional appraisal for many assets. Certain assets, particularly marketable securities, are reported at fair value with changes recognized in financial statements. This mark-to-market approach ensures balance sheets reflect current economic reality rather than outdated historical costs.

Depreciation and Amortization

Long-lived tangible assets are depreciated—their costs systematically allocated over useful lives to match expenses with revenues generated. Common depreciation methods include straight-line (equal annual amounts) and accelerated approaches (larger early-year charges). Intangible assets with finite useful lives are amortized similarly to depreciation. However, certain intangibles like trademarks and goodwill are considered to have indefinite lives and aren't amortized but instead tested periodically for impairment.

Impairment Testing

Assets must be written down when their carrying values exceed recoverable amounts. Impairment occurs when market conditions, damage, or obsolescence reduces an asset's value below its recorded balance sheet amount. Companies test assets for impairment regularly or when events suggest value declines. Recording impairment losses ensures balance sheets don't overstate asset values and that income statements reflect economic declines in resource value.

The Importance of Assets in Business Operations

Assets drive business operations and directly influence strategic decisions, making proper asset management crucial for success.

Assets and Revenue Generation

Most businesses use assets to generate revenue—manufacturers use equipment to produce goods, retailers use inventory to stock stores, and service companies use intellectual property to deliver solutions. The relationship between assets and revenue generation reveals operational efficiency. Asset turnover ratios measure how effectively companies use assets to produce sales. Higher turnover suggests efficient asset utilization, while lower ratios may indicate excess capacity or underperforming resources.

Assets and Creditworthiness

Lenders evaluate assets when determining whether to extend credit and setting interest rates and loan amounts. Lenders may factor in a company's assets when issuing loans, viewing them as potential collateral and indicators of financial stability. Companies with substantial asset bases generally access credit more easily and on favorable terms compared to asset-light businesses. Tangible assets like real estate and equipment provide particularly strong collateral since lenders can seize and sell these resources if borrowers default.

Assets and Business Valuation

Company valuations heavily weight asset values and quality. Investors analyze balance sheets to understand what they're purchasing—cash generates immediate returns, receivables convert to cash soon, while property and equipment support long-term operations. Asset-heavy companies in manufacturing, transportation, and real estate typically command different valuations than asset-light technology and service businesses. Understanding asset composition helps investors determine appropriate valuation multiples and risk assessments. For complex asset accounting scenarios, tools like Accounting Assignment Help can provide guidance on proper classification, valuation, and financial statement presentation.

Common Asset Accounting Challenges

Proper asset accounting involves navigating various challenges that require professional judgment and adherence to accounting standards.

Determining Asset Recognition

Not every resource controlled by a business qualifies for balance sheet recognition. Items must meet specific criteria including probable future economic benefits, reliable measurement capability, and result from past transactions or events. However, some assets are acquired at such a low cost that it is more efficient from an accounting perspective to charge them at once. The materiality concept allows immediate expensing of items that would technically qualify as assets but whose value doesn't justify tracking over multiple periods.

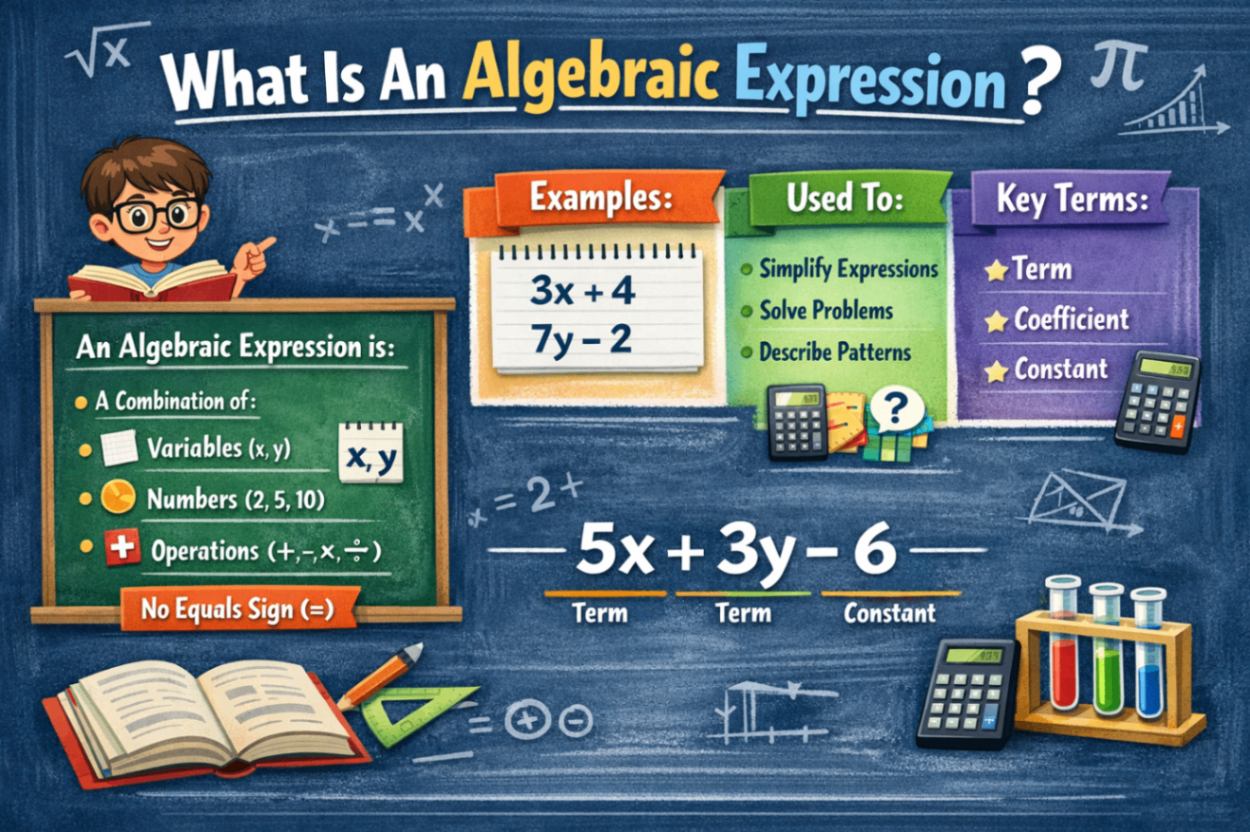

Distinguishing Assets from Expenses

The distinction between assets and expenses fundamentally affects financial statements. An asset is an expenditure that has utility through multiple future accounting periods. If an expenditure does not have such utility, it is instead considered an expense. For example, purchasing office supplies creates an immediate expense if supplies will be consumed quickly. However, purchasing a computer system represents an asset since it provides benefits over several years. This judgment requires understanding both the resource's nature and expected benefit period.

Intangible Asset Valuation

Valuing intangibles presents significant challenges since most lack active markets providing reference prices. How does one value brand recognition, customer loyalty, or proprietary processes developed internally? These valuation difficulties mean many valuable intangible assets never appear on balance sheets. Only intangibles acquired in transactions or created through specific legal protections like patents get recognized, potentially understating true economic resources.

Asset Impairment Recognition

Deciding when assets have declined in value below their carrying amounts requires significant judgment. Companies must monitor for impairment indicators—adverse market changes, competitive pressures, damage, obsolescence, or underperformance. Conservative impairment recognition protects financial statement users by ensuring assets aren't overstated. However, premature impairment charges can understate asset values and distort performance measurement, requiring balanced professional judgment.

Conclusion

Understanding what is an asset in accounting provides an essential foundation for interpreting financial statements and making informed business decisions. The definition of an asset encompasses resources controlled by entities from past transactions that are expected to provide future economic benefits, whether through revenue generation, cost reduction, or exchange value. Assets are classified multiple ways—current versus non-current based on timing, tangible versus intangible based on physical existence, and operating versus non-operating based on usage—with each classification serving specific analytical purposes. What is considered an asset in accounting requires meeting recognition criteria including probable future benefits and reliable measurement, distinguishing assets from expenses that lack multi-period utility. From cash and inventory to property and intangible assets like patents, these resources collectively determine business net worth, borrowing capacity, and operational capability. Proper asset valuation using historical cost, fair value, depreciation, and impairment principles ensures balance sheets accurately represent economic reality while adhering to accounting standards. Whether you're managing business resources, analyzing investment opportunities, or studying accounting fundamentals, mastering asset concepts enables you to assess financial health accurately and understand how businesses deploy resources to create value and drive sustainable growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

What qualifies as an asset in accounting?

An asset must meet three criteria to qualify for balance sheet recognition: it must be controlled by the entity (not necessarily owned), result from past transactions or events, and be expected to provide future economic benefits through revenue generation, cost reduction, or exchange for other valuable resources. Control represents the critical element—the business must possess the ability to obtain benefits from the resource and prevent others from accessing those benefits. Assets range from physical items like equipment and inventory to intangible resources like patents and customer relationships, all sharing the characteristic of contributing to business value.

What is the difference between current and non-current assets?

Current assets are resources expected to be converted to cash, sold, or consumed within one year or the business's operating cycle, whichever is longer. These include cash, accounts receivable, inventory, and prepaid expenses that support day-to-day operations. Non-current assets, also called fixed or long-term assets, provide benefits over extended periods beyond one year and include property, equipment, long-term investments, and intangible assets like patents. This classification helps stakeholders assess liquidity and understand how quickly a company can access cash from its resource base.

How do tangible assets differ from intangible assets?

Tangible assets have physical form that can be touched and seen, including cash, inventory, buildings, equipment, and land. These physical resources are generally easier to value since markets exist for most tangible items. Intangible assets lack physical substance but still hold value, including patents, copyrights, trademarks, brand names, customer relationships, and proprietary technology. While intangibles can be extremely valuable—sometimes more so than physical assets—they present valuation challenges since no active markets exist for many unique intellectual properties, requiring specialized appraisal techniques.

Why are assets important for business financial health?

Assets represent the resources available to generate revenue, meet obligations, and fund growth. They form the foundation of business net worth in the accounting equation where assets equal liabilities plus equity. Lenders evaluate asset levels and quality when making credit decisions, often requiring asset collateral for loans. Investors analyze assets to understand business capabilities and assess valuation—asset-heavy manufacturers differ fundamentally from asset-light technology companies. Strong asset bases indicate financial stability and operational capacity, while insufficient assets relative to liabilities signal solvency concerns that may threaten business survival.

Can employees be considered assets in accounting?

No, employees cannot be recognized as assets on balance sheets under traditional accounting standards. Human resources are not considered assets because they cannot be owned or controlled in the same way as physical or financial resources. Despite their value to an organization, employees do not meet the recognition criteria for assets under accounting standards. While employees undoubtedly create value and represent critical resources, businesses don't control them the way they control equipment or intellectual property—employees can leave at any time, and businesses cannot sell, transfer, or exchange their workforce like other resources.